Rebuilding NOLA (New Orleans, Louisiana)

By Jane Schaller

Pastor Nicole Lamarche's nimble feet were ready to roam. After years of embracing community outreach with funds raised through her Cotuit Federated Church projects, it was time to step outside of the comfort zone and tread alongside Jesus.

Nicole soon found common ground with two other United Church of Christ pastors—Reed Baer of West Parish, Barnstable and Fred Meade of North Falmouth Congregational Church, North Falmouth—by planning a mission to New Orleans to help rebuild homes left devastated by hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005. Rev. Meade was a pastor at a church in New Orleans when catastrophe hit and this would be his first time back since the ordeal. Each congregation agreed to send seven volunteers to work at St. Bernard Project, in the area most hit by the storm, St. Bernard Parish—during the week of April 17-24—school vacation time for many.

Plans for the mission had been in place for many months, when one of those going from Cotuit had to bow out for medical reasons. Pastor Nicole asked her congregation for offers to take his place; thinking only with my heart I followed its lead to be their seventh. Although new to the church, I had been immersed in community volunteer work for much of my life and this opportunity felt like a perfect fit.

Church-based community outreach commonly embraces the needs of its immediate neighborhood, as do local government agencies. The decisions about how responsibilities are divided are dependent upon the amount of funds available, as well as the immediate interests and needs of local residents. These accepted local outreach boundaries evaporated before American's collective eyes as the swift demise of human normalcy unfolded in front of the television cameras. Like Russian nesting dolls of increasing sizes that fit perfectly inside of each other, the levels of community outreach, meld together to aid others in need, regardless of imposed boundaries.

After arriving in New Orleans, we made our way in three rented minivans to St. Mark's Church, where housing is offered to those helping with the rebuilding effort. Genders parted company at the doors of community bunking rooms, with guys sleeping on rows of bunk beds in one room, the gals across the way. Down the hall, adjacent to a grand sitting room, were gender-specific bathrooms complete with showers and laundry facilities. We would gather after evening meal in the sitting room to reflect on the day's events. Pastor Nicole brought along hymns to sing and soothing candles to ignite our inspirations. Every evening, the groups made lunches for the next day after enjoying a hearty group meal prepared by different volunteers rotating sign-up shifts—including clean up and shopping detail.

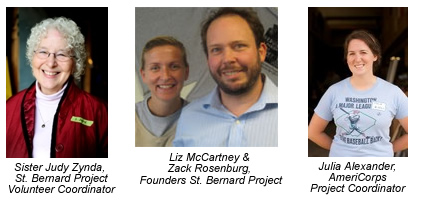

The Cape Cod church contingent spent its first afternoon as tourists in the French Quarter before joining fellow volunteers from numerous locales around the country, for a compelling orientation, led by St Bernard Project Volunteer Coordinator, Sister Judy Zynda.

"Everyone in St. Bernard has a story," she related to the crowd.

"But it is the same story: 'I lost my home and everything in it'." We listened intently, gradually absorbing the grim reality of what has occurred and continues to amass in the neighborhoods hardest hit by the storm that struck nearly five years ago.

"On most blocks one encounters no people, hears no human sounds." Sister Judy continued warily. "There are no dogs or cats. The odd car prowls by, picking its way amid potholes. By day, people come and work on their houses. By night, the sense of desertion is overpowering. Even a graveyard feels less desolate, because it is not meant for living."

Crucial to the massive storm damage was the construction--in 1958-1968, then de-authorization in June 2008--of the MRGO (Mississippi River Gulf Outlet) navigation channel. The dredging through shallow bays, coastal marshes and cypress swamps, which would have normally protected the levee system, caused the channel to serve as a funnel, resulting in the 15-19 foot surge that engulfed New Orleans.

By chance, St. Bernard Parish was the only region completely inundated, resulting in:

- Waters rising 6-20 feet, remaining so for 2-4 weeks.

- 100% of the community's homes were officially rendered uninhabitable.

- Families in St. Bernard Parish lost everything: houses were flooded; possessions were destroyed; tools and methods for livelihoods ruined.

- More than 200 residents of the Parish lost their lives as a result of the hurricane.

Evacuation of stunned families in the weeks following the horrors of Katrina, sent once-cohesive, settled family units into scattered directions (Salt Lake City, Boston, Houston). While it was generous of outside communities to offer shelter and comfort to those in need, most refugees longed to just go home.

Months later--after being allowed to return to St. Bernard Parish--the nightmare of missing infrastructure was encountered. Despite such overwhelming obstacles, the residents refused to allow their spirits to be dampened and remained determined to rebuild their lives. Many assumed that the government would follow through on promises to fund rebuilding efforts but the sobering reality of ineffective, hindered big government bureaucracy sunk in as more months clicked by.

The myriad of procedural obstacles included:

- Flood Insurance – A year before hurricane Katrina, St. Bernard Parish was zoned out of the flood plain—levees were determined to be suitable—along with the fact that there had been no significant storms since Hurricane Betsy in 1965. Residents were informed that they no longer needed flood insurance, so many cancelled their policies.

- The Road Home Program ran out of money, causing a number of residents to not receive funds after years of waiting.

- Homeowner's Insurance – typically covers only above the water line and these residents—on average-- were 21 feet below it.

- Some families were able to hire contractors with money saved but they were frequently required to pay fifty per cent of cost to begin work –then, often workers abandoned the jobs with the funds or left the work unfinished.

- Rental property as well as temporary housing and FEMA trailers were scheduled to be removed.

Seasoned Washington DC community activists, Liz McCartney and Zack Rosenburg made their way to the devastation months after humanity was allowed back to the site of destruction. Determined to bypass government red tape, they summoned American grass roots spirit by quickly establishing the means for hardworking residents to return to their homes. In March 2006, the pair created St. Bernard Project, an organization whose goal is to provide crucial resources and support to the community in the most efficient way possible.

Starting out with a few helpers, rebuilding one home at a time, the organization has grown to include the permanent presence of AmeriCorps volunteers. AmeriCorps is a federal government program consisting of impressive young men and women receiving a living stipend, who have chosen to serve their country by giving back to those who need it the most.

Twenty two year old Project coordinator and AmeriCorps volunteer, Julia Alexander affirms "It is tough work, seeing the thousands of unoccupied houses every day, working with clients who have suffered many mental and physical injuries following the storm. But we know that everyone serving together makes the hard work even more satisfying."

After the riveting orientation, St. Bernard Project coordinators split our troupe of 21 into three groups, based on skill sets and needs of the homeowners. Our determination to make a difference was strengthened by the knowledge that St. Bernard Project has rebuilt the homes and lives of more than 270 families in the New Orleans region, and has other fifty-plus homes under construction.

Each group was driven to the respective homes by one of the three pastors. As our rented minivan tires sped away from the protective umbrella of hospitable volunteer coordinators, we knew two things for sure—life would never be the same and no matter what, we were going to help rebuild NOLA.

Next installment in the Holiday issue of CWO: Jane Schaller relates her personal perspective of Rebuilding NOLA as a St. Bernard Parish volunteer.

The problems in the New Orleans

area are solvable. Please be

part of the solution.

Text N-O-L-A to 50555

and donate $5 to

St. Bernard Project

With this money, we can help bring more families home.

Jane Schaller is our 'web princess' and a contributing writer for this magazine. She has an AS in Web Design and Development from Cape Cod Community College.

She is a copy editor at Cape Cod Life magazine and freelance writer. Mother to three grown daughters, she resides in the Web Princess palace with her two dogs three cats and husband of 36 years.

|