Packed in a Trunk

by Jane Anderson

I've had the privilege of living with a Provincetown artist for the past fifty years of my life.

She died when I was only three, but her paintings hung on the walls of the house where I grew up. They now hang in my home here in the Hollywood Hills, a good 3,000 miles away from where she first set up her easel on the Provincetown beach almost a hundred years ago.

You've never heard of Edith Lake Wilkinson. At the age of 57 she was committed to an asylum. Her art, along with all her worldly possessions, was packed up in a couple of trunks and shipped off to her sole surviving relative, a nephew in West Virginia. Edith was never heard from again. The trunks sat in an attic for the next 40 years, shut tight and collecting dust.

And then my mother showed up.

Some time back in the early '60's, my mother was having one of those bored, restless days, visiting the in-laws in Wheeling. She proposed to my Aunt Betty that they go up to the attic of Grandma's three-story house and see what treasures they could dig up.

When my mother asked Aunt Betty what was in the trunks, she said, "Oh, I don't know, just some old junk." She told my mother that the trunks belonged to Uncle Eddie's long-forgotten maiden aunt. No one in the family ever spoke about poor Aunt Edith. She had been shut away in a mental institution and that was just something that nice families didn't talk about.

But when my mother opened the trunks, she found dozens of Edith's light-drenched canvases tucked in with her moldering clothes. Having an eye for beautiful things, my mother told my aunt to get those paintings framed and up on a wall. Thankfully, Aunt Betty took her advice. She kept some for herself and gave the rest to my mother who took them back to California.

I grew up surrounded by Edith's art. They were the backdrop of my childhood. Her palette, her brush strokes, the quality of light in her landscapes became part of my own visual vocabulary. She taught me that the colors in a shadow are as gorgeous as anything that's lit by the sun.

I painted with her brushes that my mom had retrieved from her trunks. I ended up wrecking every last one of them but I don't think Edith would have minded. If you look at the studies she did of children, you can see that she had a soft spot for kids.

Publisher's Note: This is one of those stories that just screams to be told. It is why I love to publish this magazine. Jane Anderson introduces us to the artist Edith Lake Wilkinson, giving a voice to a woman who was silenced in the prime of her artistic life.

If you would like to help Jane bring Edith's work home to Cape Cod, where it belongs, please email me at Nicola@capewomenonline.com

She even let a child draw a silly duck on the page of one of her sketchbooks. She must have been a gentle, playful, curious soul.

I moved to New York City when I was twenty – the same age that Edith was in 1889 when she left her home in Wheeling to study at the Art Students League. I kept notebooks filled with subway riders, bag ladies, scenes from Central Park and the Lower East Side.

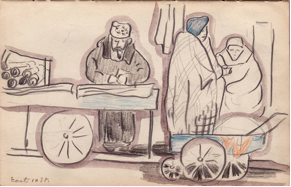

Around that time, my aunt and uncle let me root through their closets and drawers for any more scraps of Edith that I could find. It was then that I found her sketchbooks and was astonished to see that sixty years earlier, Edith had been wandering those same streets sketching the people she saw: street vendors, immigrant women with their children, uptown ladies arranged on park benches. It was clear that we were visual soul mates. I set out to find out as much about Edith as I could.

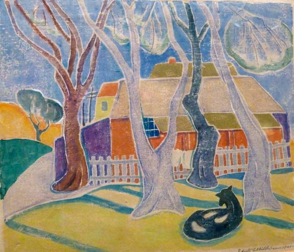

Around 1914 Edith joined the summer artists' colony in Provincetown and turned from her sooty New York palette to filling her canvasses with that remarkable Cape Cod light. Edith discovered white-line printmaking and produced some remarkable pieces. She eventually moved from the airy, layered stippling of Impressionism to the saturated boldness of the Fauves.

In 1923 Edith was still spending her summers in P-town and living the rest of the year in Manhattan with her longtime companion, Frannie. And then the next year, inexplicably, she was sent to Shepard Pratt Institute in Baltimore. She was released for a short time and then she went back in.

I found whatever records I could from the two asylums where Edith was sequestered. The only prognosis I found was a single word in blurry type: "depression." I found a letter from the Wilkinson family lawyer who was in charge of Edith's estate and busily absconding all of her funds. In the letter to Edith he advised her against living with Frannie.

Edith was gay, which made her vulnerable to the whims of a crooked lawyer who no doubt had a hand in sending her off to the nut house. As it turned out, the fellow ended up doing prison time for bilking a long list of clients. But it was too late for Edith. She never left the asylum. She had no more contact with Frannie and her life as an artist was done.

I've been to Provincetown over the years, looking for traces of Edith. I've shown slides of her work to curators and gallery owners, searching for clues. No one had ever heard of her. And frankly, no one much cared. She was an unknown and her art had no value.

I took a long break from Edith. I had my own career as a writer to worry about. I packed up her work and moved to L.A. But years later, her work is still up on the walls of the house that I share with my spouse Tess and our son. Edith's paintings are a witness to my own happy life.

I've benefited from all those grand social movements that have given women of my proclivities the freedom to live however we damn well please. I'm now in my late 50's, the age when Edith was put away. I'm still productive and I'm very much loved. I have the life that Edith should have had.

And so I've taken up Edith's cause once again. But this time I don't have to carry slides of her work from door to door. I have the miraculous tool of the Web. I've created a site for Edith where you can view her work. Please take a look. Then pass it on. http://www.edithlakewilkinson.com

But my ultimate goal is to return Edith to Provincetown where she once lived and thrived as an artist. If there's any justice in this world, she'll have a place on a gallery wall next to her more celebrated brethren.

Here's to lifting all the lost and gifted souls of this world out of attics and closets and forgotten rooms.

Here's to being seen.

All images courtesy of Jane Anderson

Jane Anderson is an award-winning playwright, screenwriter and film director who currently lives in Los Angeles.

If you would like to help Jane bring Edith's work home to Cape Cod, where it belongs, please email the publisher at Nicola@capewomenonline.com

|